The background behind the Anglo Spanish war

In 1622, Philip IV reigned in Spain, with Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares as his favourite. The War of Flanders had reignited after the Twelve Years’ Truce, and Spain’s finances flowed from its imports of silver from its American colonies. James I was King of England, Scotland and Ireland, with his son Charles, Prince of Wales, as his heir. At this time the Kingdom of England had military ties with the United Provinces, which they had assisted in the War of Flanders.

Around this time a series of events unfolded resulting in the resumption of hostilities between the two kingdoms. During the Thirty Years’ War which broke out in Europe, Frederick V of the Palatinate and his wife Elizabeth Stuart, the daughter of the King of England, were defeated and dispossessed by the Spanish Tercios.

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, accompanied the Prince of Wales on a trip to Madrid to arrange the details of the proposed wedding between Charles and Maria Anna of Spain, however these negotiations proved unsuccessful. Following the trip to Spain, the two switched positions and began advocating war with Spain. They persuaded King James to summon a new Parliament which would be invited to advise on foreign policy. The resulting Parliament of 1624 was, at least in the short run, a triumph for Charles and Buckingham, as it strongly advocated war with Spain.

However, James had a dilemma stemming from mutual distrust between himself and Parliament. He feared that if he went to war, Parliament would find an excuse to avoid providing the finances to support it. Parliament, on the other hand, feared that if it voted the finances, the King would find an excuse not to go to war. James died shortly afterwards, leaving foreign policy in the hands of Charles, who rather naively assumed that if he followed the policy that Parliament had advocated, it would provide the funds for it. The 1624 Parliament voted three subsidies and three fifteenths, around £300,000 for the prosecution of the war, with the conditions that it be spent on a naval war. James, ever the pacifist, refused to declare war, and in fact never did. His successor, Charles I, was the one to declare war in 1625.

The attack

War was duly declared on Spain, and Buckingham began preparations. The plan was put forward because after the Dissolution of the Parliament of 1625, the Duke of Buckingham, Lord High Admiral, wanted to undertake an expedition that would match the exploits of the raiders of the Elizabethan era and in doing so, would return respect to the country and its people after the political stress of the preceding years. The planned expedition involved several elements, including overtaking Spanish treasure ships coming back from the Americas loaded with gold and silver and then assaulting Spanish towns with the intention of causing stress within Spain’s economy and weakening the Spanish supply chain and resources in regards to the Electorate of the Palatinate.

By October 1625, approximately 100 ships and a total of 15,000 seamen and soldiers had been readied for the Cádiz Expedition. An alliance with the Dutch had also been forged, and the new allies agreed to send an additional 15 warships commanded by William of Nassau, to help guard the English Channel in the absence of the main fleet. Sir Edward Cecil, a battle-hardened soldier fighting for the Dutch (who fought also at the Battle of Nieuwpoort), was appointed commander of the expedition by the Duke of Buckingham. The choice of commander was ill-judged because Cecil was a good soldier but had little knowledge of the sea. the Dutch part was under Willem van Nassau-LaLecq, the illegitimate son of Maurits, who was appointed admiral in 1625. Laurens Reael was appointed vice admiral.

The expedition began from Plymouth Sound on 6 October 1625, but the voyage was plagued with difficulties. Stormy weather threatened the ships, rendering many of them barely seaworthy and causing major delays. By the time the fleet escaped from the storms and arrived in Spanish waters, it had become apparent that they were too poorly supplied to conduct the mission properly and that they were too late to engage the West Indian treasure fleet because of the storms they had encountered; in any case, the treasure fleet had used a more southerly passage than usual.

Edward Cecil

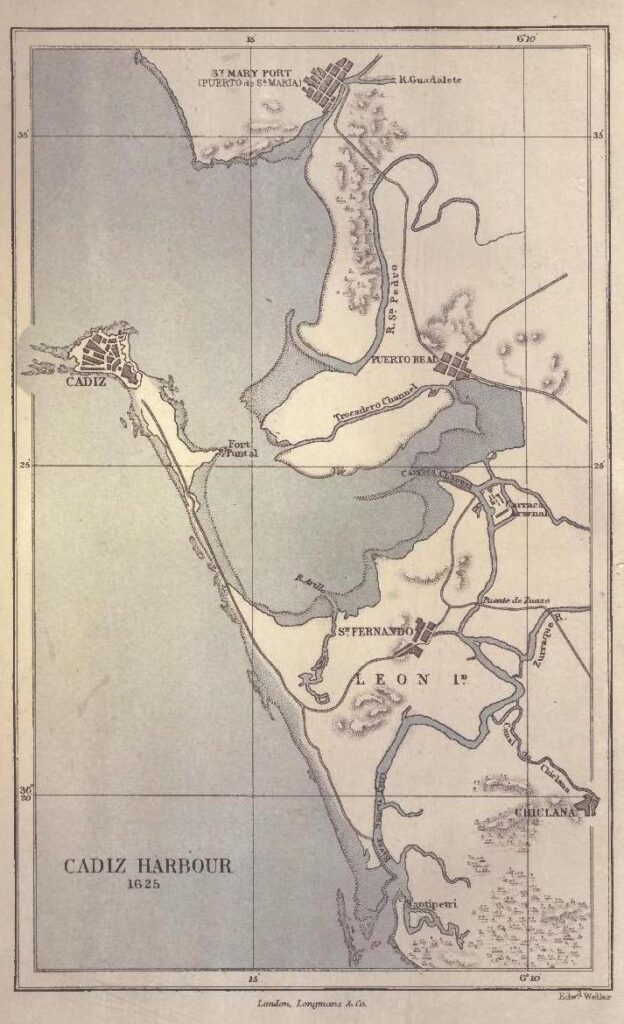

Cecil chose to assault the Spanish city of Cádiz and after successfully sailing to the Bay of Cádiz and landing his force, he was able to take the fort that guarded the harbor of the city. However, he soon found that the city itself had been heavily fortified with modern defences, and it then began to make serious errors. Spanish vessels that were open to capture were able to get away because most of his forces waited for orders and did not act. The Spanish ships then sailed to the safety of Puerto Real, in the easternmost anchorage of the bay.

The ships used in the assault were also largely merchant vessels conscripted and converted for warfare, and the captains or owners of those ships, concerned about the welfare of their ships, left much of the battle to the Dutch. The attack on and capture of El Puntal tower proved a mistake, as that fortification did not need to be captured to be able to attack Cádiz.

Fernando Girón de Salcedo

When Cecil landed his forces, they realised that they had no food or drink with them. Cecil then made the foolish decision to allow the men to drink from the wine vats found in the local houses. A wave of drunkenness ensued, with few or none of Cecil’s force remaining sober. Realizing what he had done, Cecil took the only course left open to him and ordered that the men return to their ships and retreat. When the Spanish army arrived, they found over 1,000 English soldiers still drunk; although every man was armed, not a single shot was fired as the Spanish put them all to the sword.

Fernando Girón de Salcedo y Briviesca was the Spanish governor would successfully defended Cádiz, which led him to be immortalized in a painting of Francisco de Zurbarán, The Defence of Cádiz against the English. In 1626 the King made him the first marquess of Sofraga, for his services to the Realm and to His Majesty personally.

After the embarrassing fiasco of Cádiz, Cecil decided to try to intercept a fleet of Spanish galleons that were bringing resources back from the New World. That failed as well because the ships had been warned of danger in the waters and so were able to take another route and returned home without any trouble from Cecil’s ships. Disease and sickness was sweeping through the ranks, and since the ships were in a bad state, Cecil finally decided that there was no alternative but to return to England although he had captured few or no goods and made little impact on Spain. Therefore, in December, the fleet returned home; the expedition had cost the English over 1000 men, 30 ships and an estimated £250,000.

Aftermatch

The failure of the attack had serious political repercussions in England. Charles I, to protect his own dignity and his favourite, Buckingham, who should have at least made sure the ships were well supplied, made no effort to enquire about the failure of the expedition. He turned a blind eye but instead interested himself in the plight of the Huguenots of La Rochelle. The House of Commons was less forgiving. The Parliament of 1626 began the process of impeachment against Buckingham. Eventually, Charles chose to dissolve Parliament rather than risk a successful impeachment.

England altered its involvement in the Thirty Years War by negotiating a peace treaty with France in 1629. Thereafter expeditions were undertaken by the Duke of Hamilton and Earl of Craven to the Holy Roman Empire in support of the thousands of Scottish and English mercenaries already serving under the King of Sweden in that conflict. Hamilton’s levy was raised despite the end of the Anglo-Spanish War. In addition English troops would constitute a large part of the States army but in their pay after 1630. In the following years under Frederick Henry and Horace Vere the cities of Maastricht and Rheinberg were recaptured.

With the advent of the War of the Mantuan Succession Spain sought peace with England in 1629 and so arranged a suspension of arms and an exchange of ambassadors. On 15 November the Treaty of Madrid was signed which ended the war and thus restored the ‘Status quo’. It had proven a costly fiasco for England, whose merchants lost the profitable Flemish cloth markets to heavy custom duties after the war. The unsuccessful and unpopular outcome of the conflict fuelled the disputes between the Monarchy and Parliament that began before the English Civil War, to the point that the first charge against Charles I in the Grand Remonstrance was about the costs and mismanagement of the 1625 war with Spain.